Programmatic Analysis

The Title "Titan"

Johann Paul Friedrich Richter

"Titan" is a reference to Jean Paul’s great novel of the same name. "Titan" was included in the title of the symphony’s second (Hamburg) and third (Weimar) performances, after which it was permanently removed. How significant the relationship between the program, Jean Paul and specifically his novel Titan remains a question open to debate. There is however, no doubt that Mahler was a great admirer of Jean Paul’s works.

Bruno Walter stated that he and Mahler "often talked about the great novel [Titan], especially the figure of Roquairol, whose influence is noticeable in the funeral march of the First and who was the subject of detailed discussion."

Literary references can be found between the program notes and Jean Pauls’ novels. For example the title Blumen-, Frucht- und Dornenstücke refers to Jean Paul's novel Siebenkäs, and title "Blumine" takes its name from Jean Paul's Herbst-blumine.

First Edition of Jean Paul's work: Titan.

According to Josef B. Foerster, Mahler drew much inspiration for the creation of the first symphony from impressions he gained reading the works of Jean Paul. As a sign of gratitude, Mahler included the title from the novel "Titan", the book which had been the greatest source of inspiration for the symphony. Foerster also suggested that Mahler included the title for the Hamburg and Weimar concerts as he believed Jean Paul’s works would have been familiar to the audiences there.

However, Natalie Bauer-Lechner understates the impact Jean Paul’s work had on the symphony, writing: "What he had in mind was simply a strong, heroic person, living and suffering, struggling with and succumbing to destiny, for which the true, higher resolution is not given until the Second [Symphony]".

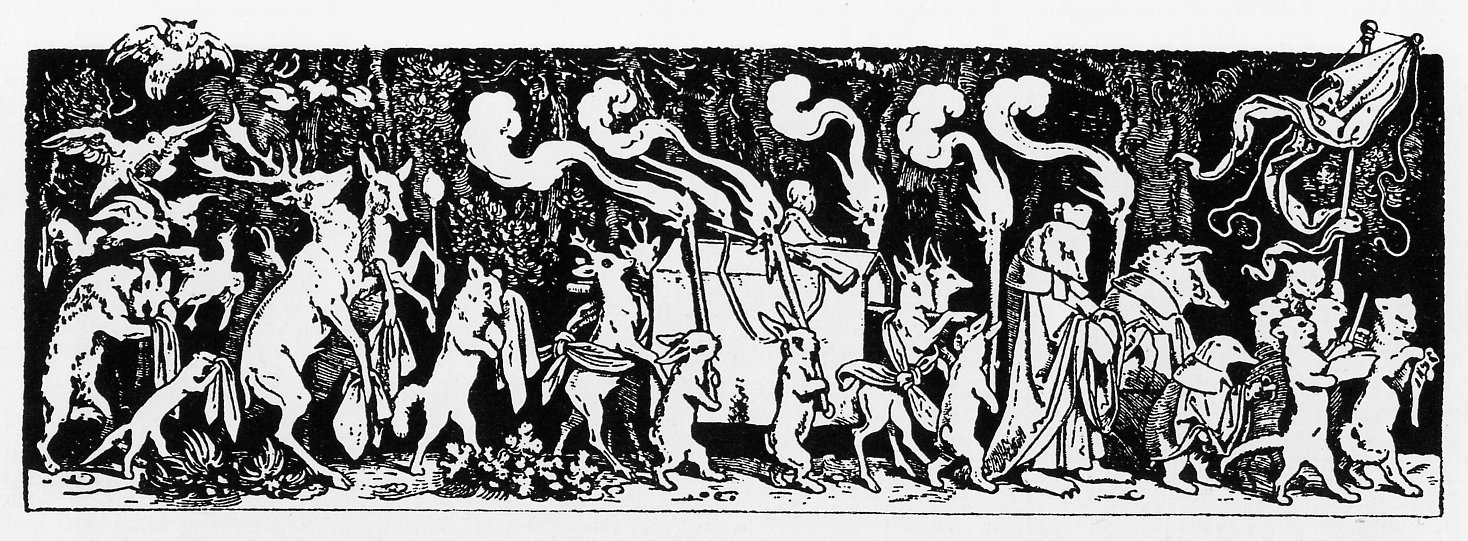

Funeral March

The picture above is a wood-cut depiction of ‘The Hunter’s Funeral Procession’ story by the Austrian artist Moritz von Schwind created in 1850. It helped inspire the Funeral March movement. The second part of the title for this movement is: Funeral March in the Manner of Callot. It is likely that Mahler wrongly attributed the above wood-cut as being a creation of the printmaker Jacques Callot, whilst slipping a further reference to Jean Paul who had written the preface to E.T. A. Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier [‘Fantasy Pieces in the Manner of Callot’] in 1815.

The Hunter's Funeral Procession title for the third movement of the Weimer version refers to an old folk story that was well-known among Austrian children in Mahler’s time. Mahler wrote: "In connection with the third movement (marcia funebre)... I received the extra musical suggestion for it from the well-known nursery picture (The Hunter's Funeral)... the eerie and ironical, brooding sultriness of the funeral march." These sentiments are clearly expressed musically by Mahler in the funeral march movement.

The story’s narrative is told through the eyes of forest animals and is written in a jocular character. It tells of the the burial of a hunter whose funeral procession is composed not of humans, but wild animals, including a bear, foxes, hares, a wolf, cranes and partridges, song-birds. The animals seem to derive great joy from the occasion with rabbits leading the procession holding banners and music been sung by all the animals, accompanied by the musical cats and a group of Bohemian musicians.

Mahler’s reasons for removing programmatic aspects

A direct explanation for the removal of the program notes is given by Mahler in a letter he wrote to Max Marschalk in 1896: "Originally, my friends persuaded me to supply a kind of program, in order to facilitate the understanding of the D major [Symphony]. Thus, I had subsequently invented this title and explanations. That I omitted them this time was caused not only by the fact that I consider them inadequate, but also because I found out how the public has been misled by them."

Richard Specht slated Mahler’s program notes in a review: "There is an extensive program to the First that is so extravagant, blurred, and alien to the character of the music that it seemed to come not from the composer but from one of the worst types of enthusiastic commentator."

This criticism was mirrored by the critic and composer Nodnagel from Königsberg who complained that there was no recognisable relationship between the "confused and unintelligible" program notes and the music after attending the Weimar performance.

Alma Mahler claimed that her husband Gustav was constantly asked to explain how "various situations from the novel were interpreted in the music" which caused him to remove the title.